Please note that some guidelines may be past their review date. The review process is currently paused. It is recommended that you also refer to more contemporaneous evidence.

Jaundice occurs in approximately 60 per cent of newborns, but is unimportant in most neonates. A few babies will become deeply jaundiced and require investigation and treatment.

If inadequately managed, jaundice may result in severe brain injury or death.

Jaundice early detection is important

Issue to note about jaundice:

- Early detection of jaundice (appears in the sclera with SBR of 35-40 micromol/L) may be difficult in newborns because eyelids are often swollen and usually closed.

- Jaundice may not be visible in the neonate's skin until the bilirubin concentration exceeds 70-100 micromol/L.

- Increasing total serum bilirubin (SBR) levels are accompanied by the cephalocaudal progression of jaundice, predictably from the face to the trunk, extremities and finally to the palms and soles. However, visual estimation of the degree of jaundice may be inaccurate, particularly in darkly pigmented newborns.

- Total SBR level should be used to determine management decisions in cases of predominantly unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia.

- Serum albumin level does not need to be measured in addition to the bilirubin to determine management.

- SBR from a capillary sample is assumed to be the same as that from a venous sample.

Sunlight exposure is no longer recommended as a treatment for jaundice due to risk of sunburn or overheating.

Figure 1: Jaundice in a newborn

Risk factors for developing severe hyperbilirubinaemia

Major risk factors

Major risk factors for severe hyperbilirubinaemia are:

- jaundice within the first 24 hours

- blood group incompatibility; particularly Rhesus (Rh) incompatibility

- previous sibling requiring phototherapy for haemolytic disease

- cephalhaematoma or significant bruising

- weight loss greater than 10 per cent of birthweight; may be associated with ineffective breastfeeding

- family history of red cell enzyme defects (such as G6PD deficiency) or red cell membrane defects (such as hereditary spherocytosis).

Minor risk factors

Minor risk factors for hyperbilirubinaemia are:

- jaundice occurring before discharge

- previous sibling requiring phototherapy

- macrosomic infant of a diabetic mother.

Causes of physiological jaundice

Physiological jaundice develops due to:

- increased production

- decreased uptake and binding by liver cells

- decreased conjugation (most important)

- decreased excretion

- increased enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin.

As the name implies, physiological jaundice is common and harmless.

Causes of pathological jaundice

Pathological jaundice is best considered in relation to time of birth.

1. ‘Too early’ (< 24 hours of age)

Issues to note about ‘early’ jaundice include that:

- it is always pathological

- it is usually due to haemolysis, with excessive production of bilirubin

- babies can be born jaundiced due to:

- hepatitis (unusual)

- severe haemolysis

- it causes of severe haemolysis (decreasing order of probability):

- ABO incompatibility

- Rh iso-immunisation

- sepsis

- rarer causes include:

- other blood group incompatibilities

- red cell enzyme defects such as G6PD deficiency

- red cell membrane defects, for example, hereditary spherocytosis.

If there is substantial elevation of conjugated bilirubin (> 15 per cent of the total), consider hepatitis. This may or may not occur in Rh babies who have had in-utero transfusions.

Investigation of early pathological jaundice

Investigations for early jaundice are:

- total and conjugated SBR

- maternal blood group and antibody titres

- baby's blood group

- direct antiglobulin test (Coombs) test (detects antibodies on the baby's red cells)

- elution test to detect anti-A or anti-B antibodies on baby's red cells (more sensitive than the direct Coombs test)

- full blood examination, looking for evidence of haemolysis, unusually-shaped red cells, or evidence of infection

- CRP to assist with diagnosis of infection.

2. ‘Too high’ (24 hours -10 days of age)

If the SBR concentration exceeds 200-250 micromol/L, over this time, various causes include:

- mild dehydration/insufficient milk supply (breastfeeding jaundice)

- breast milk jaundice

- haemolysis - continuing causes as discussed under ‘too early’

- breakdown of extravasated blood (for example, cephalhaematoma, bruising, CNS haemorrhage, swallowed blood)

- polycythaemia (increased RBC mass)

- infection - a more likely cause during this time

- increased enterohepatic circulation (such as bowel obstruction).

Infection

If the baby has other signs as well as excessive jaundice, acute bacterial infection must be excluded (particularly urinary tract infection).

Infections acquired early in pregnancy may cause neonatal hepatitis, but other clinical signs are obvious and a substantial fraction of the jaundice is conjugated (> 15 per cent).

Breast-milk jaundice

From as early as the third day of life, the SBR concentration of breastfed infants is higher than those who are formula-fed.

What it is in breast milk that causes excessive jaundice is not known but unsaturated fatty acids or a lipase, which inhibits glucuronyl transferase have been suspected.

3. ‘Too Long’ (> 10 days of age, especially > 2 weeks)

The major clue to diagnosis is whether the elevated bilirubin is mostly unconjugated (> 85 per cent) or whether the conjugated fraction is substantially increased (> 15 per cent of the total).

Causes of persistent unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia

Causes include:

- breast-milk jaundice (diagnosis of exclusion, cessation not necessary)

- continued poor milk intake

- haemolysis

- infection (especially urinary tract infection)

- hypothyroidism.

Hypothyroidism

Persistent jaundice may be the earliest sign of hypothyroidism in an infant.

Fortunately, all babies are routinely screened for this with the newborn screening test at 48-72 hours of age. However, if other signs suggest hypothyroidism, further investigation is mandatory because appropriate early treatment may prevent profound developmental delay.

Haemolysis

When jaundice suddenly reappears after the infant has gone home, severe haemolysis is the usual cause, particularly in infants with G6PD deficiency who are exposed to mothballs (naphthalene).

G6PD deficiency occurs most often in Mediterranean, Asian and African ethnic groups, and is more severe in males (being X-linked).

Causes of persistent conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia

Issues to note:

- A simple test of urine for bile will suggest substantial elevation of conjugated bilirubin.

- This is rare and the infant has either hepatitis or biliary atresia and requires extensive investigation.

- Conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia is always abnormal.

Hepatitis

Hepatitis can be caused by infection (toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes, or syphilis) or metabolic disorders (for example, galactosaemia).

Biliary atresia

Biliary atresia is a very rare disorder in which the bile ducts are absent, causing an obstructive jaundice which is fatal in most cases. These babies usually have pale (clay-coloured) stools and dark urine.

Prevention of jaundice

Primary prevention

Primary prevention of jaundice involves early and frequent breastfeeding (8-12 times per day for the first few days).

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention of jaundice involves the following:

- Perform a blood group, Rh (D) type and Coombs' test on the infant's (cord) blood if the mother is known to have a negative blood group or has not had antenatal blood grouping.

- Conduct a risk assessment before discharge and plan adequate follow-up.

- Monitor all infants routinely for jaundice at least 12-hourly

- Assess the risk of developing hyperbilirubinaemia prior to discharge this is especially important in infants discharged before 48 hours of age.

Monitoring of jaundice

Visual inspection

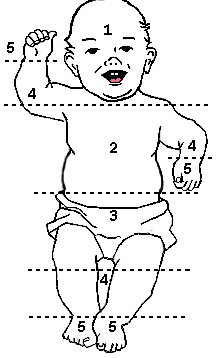

Carry out a visual inspection in natural light if possible:

- There is a normal progression of the depth of jaundice from head to toe as the level of bilirubin rises.

- Kramer's rule describes the approximate SBR level with the level of skin discolouration:

| Zone | Head and neck | Chest | Lower body and thighs |

Arms and legs below knees |

Hands and feet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBR (mol/L) | 100 | 150 | 200 | 250 | > 250 |

Figure 2: Diagram showing progression of and estimate of jaundice level according to Kramer’s rule

Figure 2: Diagram showing progression of and estimate of jaundice level according to Kramer’s rule

- Visual inspection of the infant, including Kramer's rule, can only be used as a guide to the level of jaundice.

- There is a wide inter-observer error in the clinical estimation of the depth of jaundice which should therefore not be substituted for a formal SBR measurement. The estimation is particularly unreliable in infants with pigmented skin.

Transcutaneous bilirubinometers

Transcutaneous bilirubinometers are increasingly available. Some issues to note:

- Transcutaneous bilirubinometers are most accurate at the lower levels of hyperbilirubinaemia and therefore helpful in screening and avoiding blood tests.

- Transcutaneous bilirubin estimations should only be done by staff trained in the use of these monitors.

- They may be useful for assessing infants who are jaundiced and more than 24 hours of age without risk factors for developing severe hyperbilirubinemia.

- If a transcutaneous bilirubinometer is used and the level is approaching the threshold (within 50 micromol/L) for phototherapy, a formal SBR should always be performed.

- These are only of benefit in term or near term infants and can not be used if the baby is receiving or has received phototherapy.

Need to treat guides

Prediction of likelihood of requiring treatment may be assisted by the following:

Likelihood calculators

- Bilitool - an online tool to assess the risk of developing hyperbilirubinaemia (American Academy of Paediatrics)

- Biliapp (based on NICE guidelines). Available for download from the App store or Google play.

Established nomograms

Kernicterus

Unconjugated bilirubin can be toxic to the brain and lead to the disease called kernicterus; this is characterised by the death of brain cells and yellow staining, particularly in the grey matter of the brain.

Kernicterus refers to the permanent clinical sequelae of bilirubin toxicity (see below).

The signs of acute bilirubin encephalopathy include:

- lethargy

- poor feeding

- temperature instability

- hypotonia

- arching of the head, neck and back (opisthotonos)

- spasticity

- seizures.

Death may follow.

In those infants who survive, all will have permanent brain damage, including athetoid cerebral palsy, deafness, and mental retardation.

The risk of developing kernicterus increases with:

- increasing unconjugated bilirubin - concentrations greater than 340 micromol/L are considered unsafe

- decreasing gestation - preterm infants may be at risk at lower SBR concentrations (300 micromol/L or less)

- asphyxia, acidosis, hypoxia, hypothermia, meningitis, sepsis and decreased albumin binding (serum albumin concentration too low, or binding interfered with by drugs).

Many describe a transient change in infant behaviour, even if the SBR level does not reach the level for an exchange transfusion.

This correlates with a measurable transient alteration in brainstem evoked potentials.

Available therapies

Treatment for jaundice includes:

- treatment of the cause (such as infection or hypothyroidism)

- adequate enteral hydration may reduce enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin

- if breastfed, the baby should be put to the breast between eight and 12 times per day for the first several days

- if supplementation of breastfeeding is required this should be with expressed breast milk or formula not water

- if oral intake is inadequate give intravenous fluids

- phototherapy

- exchange transfusion

- IV immunoglobulin (0.5-1 g/kg over two hours) may be given to infants with isoimmune haemolytic disease and rising bilirubin despite intensive phototherapy or bilirubin within 30-50 micromol of exchange transfusion.

Phototherapy

Exposure of jaundiced skin to light photo-isomerises the bilirubin molecule into forms which can be excreted directly into the bile, without having to be conjugated. This renders the bilirubin into a water soluble state that can be excreted in the baby’s urine and faeces.

The effectiveness of phototherapy increases with:

- blue light (460-490 nm)

- intensity of the light ( > 30 W/cm-2/nm-1, can be checked with a light intensity metre).

The greater the amount of skin exposed (circumferential exposure maximises the exposed area and thus increases clinical effectiveness, may require combined use of more than one device). Additional overhead light will only be beneficial if exposed surface area is increased.

The closer the lights to the baby (limited by risk of overheating the infant). Good-quality lights should not need to be closer than 30 cm.

The major drawback with phototherapy is that its effect is slow (despite a rapid onset of action). Phototherapy alone is rarely effective with severe haemolytic causes of jaundice where the bilirubin concentration can rise rapidly (and continue to rise despite aggressive phototherapy).

In breastfed infants who require phototherapy breastfeeding should continue.

There is no evidence to support the administration of additional fluids to jaundiced infants.

Indications for phototherapy

Issues to note include:

- Phototherapy should only be used when the bilirubin is approaching a concentration, which would usually lead to an exchange transfusion. In practice, this is 60-70 micromol/L below the exchange value.

- All infants receiving phototherapy must have a serum bilirubin level measured as well as basic investigations to exclude the common causes of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. The bilirubin level should be rechecked based on clinical assessment and medical orders; generally six to 12 hours after commencing treatment.

- Commencement of phototherapy is not an indication for transfer of infant from the postnatal ward to the special care nursery (SCN). Transfer to the SCN may be required in order to:

- provide intensive phototherapy (double or triple light therapy)

- provide specialised observation

- meet increased care requirements

- give intravenous fluids.

- The commencement of phototherapy necessitates further investigation for a cause.

'Biliblankets' may have a role in the following situations:

- outpatient management

- to allow an infant to stay in an open cot and remain with their mother on the postnatal ward

- in infants receiving intensive phototherapy to provide therapy to the area of the body that is facing away from the overhead phototherapy unit.

Monitoring phototherapy

During phototherapy infants require ongoing monitoring of:

- adequacy of hydration and nutrition

- temperature

- clinical improvement in jaundice

- potential signs of bilirubin encephalopathy.

Complications of phototherapy

Possible complications of phototherapy include:

- overheating

- water loss

- diarrhoea

- ileus (preterm infants)

- rash (no specific treatment required)

- retinal damage (theoretical)

- parental anxiety/separation

- 'bronzing' of infants with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

Ceasing phototherapy

Issues to note:

- Visual estimations of the bilirubin level or estimation by transcutaneous monitor in infants undergoing phototherapy are not reliable.

- Infants can tolerate higher SBR once sepsis and haemolysis excluded in well term baby.

- Cease phototherapy when SBR is at least 50 micromol/L below the phototherapy range (generally less than 240 micromol/L).

- Rechecking the bilirubin level after cessation is not usually required unless increased risk of significant rebound:

- haemolytic disease

- gestation less than 37 weeks

- cessation of phototherapy at less than 72 hours of age.

Discharge from hospital need not be delayed to observe rebound of bilirubin.

Exchange transfusion

Since exchange transfusions are rarely performed today, especially outside tertiary health services, it is strongly recommended that any baby who requires an exchange transfusion be transferred to a tertiary centre.

Indications Rh disease

Exchange transfusion should be considered in infants with Rh disease who:

- have not received blood transfusions in utero

- have cord blood haemoglobin < 100 g/L

- have cord bilirubin > 80 micromol/L

- are visibly jaundiced within 12 hours of birth.

These infants are at high risk of needing an exchange transfusion and preparations should be made (lines inserted, blood ordered) while a formal SBR level is urgently ordered.

The effects of intrauterine transfusions are unpredictable, but haemolysis is usually less severe because more of the baby's blood is Rh negative donor blood.

Indications - other

Indications for exchange transfusion in well, term infants are:

- bilirubin >340 micromol/L

- likely to exceed that concentration for any length of time

- see the threshold graphs.

In preterm or sick infants, lower concentrations of bilirubin may warrant exchange transfusion.

Infants manifesting the signs of intermediate to advanced stages of acute bilirubin encephalopathy, even if the bilirubin level is failing.

Risks of exchange transfusions

Risks of exchange transfusion (although uncommon) include:

- apnoea

- bradycardia

- cyanosis

- vasospasm

- air embolism

- infection

- thrombosis

- necrotising enterocolitis

- death (rarely).

These risks are higher in sick, preterm infants.

After an exchange transfusion subsequent monitoring of the haemoglobin is necessary because ongoing haemolysis may result in significant anaemia, and the baby may still need a number of top-up simple blood transfusions.

More information

References

- American Academy of Paediatrics. Clinical Practice Guideline. Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinaemia: Management of hyperbilirubinaemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Paediatrics 2004;114:297-316

- Deshpande PG. Milk Jaundice http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/973629Breast Updated Apr 8, 2010

- Maisels MJ, Watchko JF. Treatment of jaundice in low birth weight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003;88:F459-63

- Statewide Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program. Neonatal jaundice: prevention, assessment and management. http://www.health.qld.gov.au/cpic/resources/mat_guidelines.asp. Published Nov 2009

- SA Perinatal Practice Guideline Chapter 83 Neonatal Jaundice, Government of South Australia, August 2010.

- Neonatal jaundice (NICE guidelines)

- Jaundice and your newborn baby - The Royal Women's Hospital Fact Sheet

Get in touch

Version history

First published: July 2014

Review by: July 2017